p. 7We conceived of this issue, “Art beyond Copyright,” nearly two years ago. Our position was and remains, first, that copyright law stands in direct opposition to art historians and is irrelevant to the vast multitude of practicing artists; and, second, that the myopic focus on copyright has blinded attention to conceptually and historically distinct facets of the law that inflect art practice, art history, and art law. The inadequacy of copyright and the imperative to seek out alternatives for art and law are the focus of this special issue of Grey Room.

In the years since we began work on this issue, two major developments have made the issues we address here even more urgent. First, the Supreme Court of the United States heard and decided Warhol v. Goldsmith, its first-ever case on visual art and “fair use” in copyright, a question that has roiled jurists and the art world for at least thirty years. To unpack the case’s implications—and in an effort to foster conversation between the all-too-often discrete worlds of art and law—we gathered thirteen leading voices from the fields of art, art history, law, museums, and publishing. An edited transcript of our roundtable discussion, as well as an introduction to Warhol v. Goldsmith, follows on pages 21–24.

Second, generative artificial intelligence (AI) burst onto the scene.1 As rapidly evolving generative AI systems now generate billions of images based on the inputs of many more billions of images and digital data, these systems force renewed attention to the central questions posed by copyright: the meaning of authorship and of (human) creativity more generally. Generative AI presents two major sets of still unresolved and hotly contested copyright issues: whether AI companies have committed copyright infringement in using copyrighted works as part of their training data sets; and whether the images generated by AI should themselves be subject to copyright protection. But even more fundamentally, as machines now consume and produce works with startling volume and rapidity, we are living through what authors Kate Crawford and Jason Schultz call in this volume the “largest experiment in ‘art beyond copyright’ to date.”

Additionally, the interests of indigenous, traditional, colonized, and oppressed peoples and communities have gained ever greater visibility in the last years. The disconnect between copyright and p. 8 the interests of artists, addressed throughout this introduction and special issue, is even greater when those artists engage in indigenous or traditional arts and crafts. The global intellectual property regimes initiated and controlled by a succession of colonial powers—France, England, and the United States loom especially large over the last 150 years—have systematically excluded most indigenous and traditional knowledge and expression from protections, including copyright protection. As summed up in the title of Boatema Boateng’s rigorously argued book The Copyright Thing Doesn’t Work Here: Adinkra and Kente Cloth and Intellectual Property in Ghana, global copyright regimes are structured to be incapable of addressing systems of authorship and alienability, legal subjectivity, or appropriation outside dominant Western models.2 The newly visible interests of indigenous, colonized, and other oppressed peoples—not least, their resistances to the commonplace appropriations of their cultural productions—trouble the postmodern, “copyleft” rejection of copyright and suggest that new balances be struck between the rights over one’s cultural production and the rights to adopt and adapt the cultural products of others. But at a fundamental level, copyright law does not address and is ill-suited to solve these problems.3 Even when indigenous or oppressed groups succeed in asserting their intellectual property rights, the victories often risk self-exoticization and the commodification of the very cultures and identities they seek to preserve.4 What is more, the multifarious practices, artifacts, and sites recognized as cultural heritage or cultural property not only lie largely outside of copyright but also, as Patty Gerstenblith notes in these pages, often outside the direct purview of the law.

But even before any of these developments, the relationship between art and copyright was strained to the point of breakdown. The gaps and limitations of copyright for Warhol, AI, and indigenous and traditional cultural production speak to the two concerns that compelled us to begin this project: the broader and more fundamental misfit of copyright law for art and the inadequacy in limiting the nexus of art and law to the realm of copyright. In this special issue of Grey Room, we hope to elucidate and begin to rectify these problems in the current discourses around art and law. In this introduction, we begin by briefly rehearsing the basics of copyright law, with a focus on the United States. Most of the contributions in this volume operate within a U.S. legal framework, but snippets of global intellectual property law are evident in Stina Teilmann-Lock’s article on design patents, Gerstenblith’s on cultural heritage, Noam Elcott’s on French and English trademarks, and in various comments made during the roundtable. The most significant difference between common law copyright (anchored in U.K. and U.S. law) and civil law copyright (anchored in French and Continental European law) p. 9 is the bundle of rights known as droit d’auteur, especially “moral rights.” After setting forth this account of law, we then turn to the serious limitations and insufficiencies of copyright as it pertains to art practice and art history. Ultimately, we aim not only to expose the limits of copyright law but also to open new paths for the pursuit of art, art history, and art law.

| | | | |

Similar to other jurisdictions, copyright law in the United States protects “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression,” including literary works, visual works, sound recordings, and movies.5 A copyright holder receives, among other things, the exclusive right to reproduce the work, display it, distribute copies, and prepare “derivative” works.6 Copyright typically endures until seventy years after the author’s death.

Unlike in civil law jurisdictions, American copyright law has come to be understood almost universally in utilitarian terms. According to this peculiar account, rooted in a capitalist political economy, the reason we grant copyright to creators is to give them economic incentives to create culturally valuable works. As the Supreme Court explained in 1985, “By establishing a marketable right to the use of one’s expression, copyright supplies the economic incentive to create and disseminate ideas.”7 The theory is that, absent copyright, authors would not invest in creating new works because free riders could make cheap copies that would deprive the original authors of the ability to profit from their work, leaving them no economic incentive to create. Copyright steps in to prevent this, overcoming the threat that cheap copies presumably pose to innovation.

This utilitarian vision of copyright aligns with the language of the U.S. Constitution itself. The Copyright Clause gives Congress the power “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors … the exclusive Right to their respective Writings.”8 Note the distinctly public purpose behind this grant of a private right. In explaining the Copyright Clause in a 1954 decision, the Supreme Court wrote, “The economic philosophy behind the clause … is the conviction that encouragement of individual effort by personal gain is the best way to advance public welfare through the talents of authors.”9 Thus, “The monopoly created by copyright … rewards the individual author in order to benefit the public.”10

Because copyright is designed to benefit the public, and the benefit to individual creators is in some ways incidental to this goal, the law has built-in mechanisms that presumably reduce the public costs associated with the grant of private limited monopoly rights. p. 10 The costs imposed by copyright include, most prominently, the limits it imposes on public access to copyrighted works and on new creators who wish to reference or build on those works to create new ones. Yet the assumption is that these public costs are necessary because, absent copyright’s economic incentives, publicly valuable works would not be produced in the first place. Doctrines within copyright designed to mitigate these public costs include, most prominently, the idea-expression distinction, which protects the public realm of ideas by ensuring that one cannot copyright an idea but only a particular expression of it, as well as the “fair use” doctrine.11

Fair use, a notoriously unpredictable defense to a claim of copyright infringement, has gained particular prominence in copyright lawsuits that implicate the visual arts; it is the primary battleground on which high-profile copyright lawsuits involving artists such as Jeff Koons and Richard Prince have been fought.12 And it was the subject of the May 2023 Supreme Court decision in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith. (For more on Warhol and fair use, see Amy Adler’s introduction to the roundtable in this issue of the journal.) The fair use doctrine is premised on the notion that creativity sometimes requires copying. For example, in a 1994 landmark music case protecting the fair use rights of the hip-hop group 2 Live Crew to make a parody of Roy Orbison’s song “Pretty Woman,” the Supreme Court explained that fair use is “necessary to fulfill copyright’s very purpose, ‘[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.’”13 Thus the fair use defense, which allows a new creator to use copyrighted material without obtaining permission from the copyright holder, exists to temper the risk that excessively broad copyright protection would stifle rather than advance the underlying objectives of copyright.14 Yet fair use has been labeled “one of the most intractable and complex problems in all of law.”15 Indeed, some scholars have lamented that the inquiry is so “impossible to predict” as to be “useless.”16 The roundtable brings together leading scholars in law and art to discuss in depth the fair use doctrine and its implications for visual art.

Copyright law is founded on peculiar and questionable assumptions about creativity. But these assumptions break down almost completely in the context of visual art. As Adler argues in “Why Art Does Not Need Copyright” (from which the remainder of our introduction is drawn), if the purpose of copyright is to incentivize creativity, then copyright law is not only unnecessary for artistic flourishing but in fact impedes it.17

Take one of copyright’s fundamental premises: that creativity depends on economic incentives. Despite its dubious vision of human creativity, this premise at least makes economic sense when viewed from the perspective of copyright’s other core domains of p. 11 protection, such as books, music, and movies. Because writers, musicians, and filmmakers earn money from selling copies of their work, they depend on (or hope for) high-volume sales of these copies to generate income and thus need legal protection against unauthorized copies to reap value from their creations. But the theory fails when applied to visual art for a simple reason. Visual artists today make little if any of their money from copies. This is not a timeless verity but rather a historically situated fact. As Elcott argues in his article in this issue of the journal, many nineteenth-century artists did make money from copies, and it was in that historical context that copyright was first extended to artworks.

Embedded in the United States Copyright Act is a curious definition of “visual art” that helps elucidate what is at stake. The definition is part of the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990 (VARA), which grants a limited set of protections uniquely to visual artists among all types of authors. These protections, known as “moral rights,” include the right to preserve the physical integrity of a work under certain circumstances and to ensure attribution of authorship. While partially derived from civil law moral rights, which typically protect writers, musicians, and other kinds of creators in addition to visual artists, VARA protects only those who create a “work of visual art.” And the category of “visual art” is narrowly and curiously defined to include “a painting, drawing, print, or sculpture, existing in a single copy, or in a limited edition of 200 copies or fewer that are signed and consecutively numbered by the author.”18 The definition also includes photography under highly limited circumstances that loosely map onto a subset of fine art photography. VARA excludes from its protection any works that are not unique or produced in limited editions.

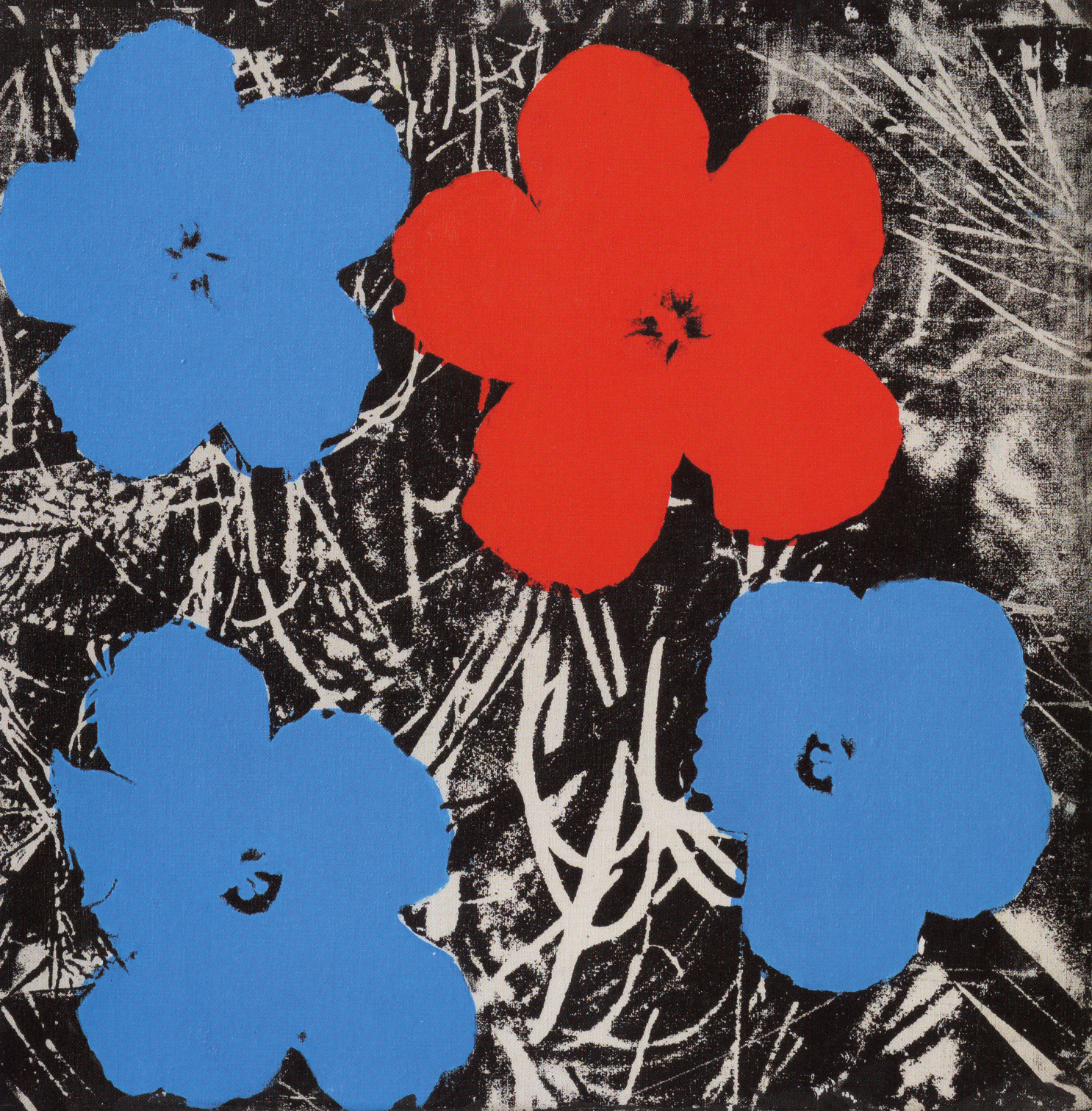

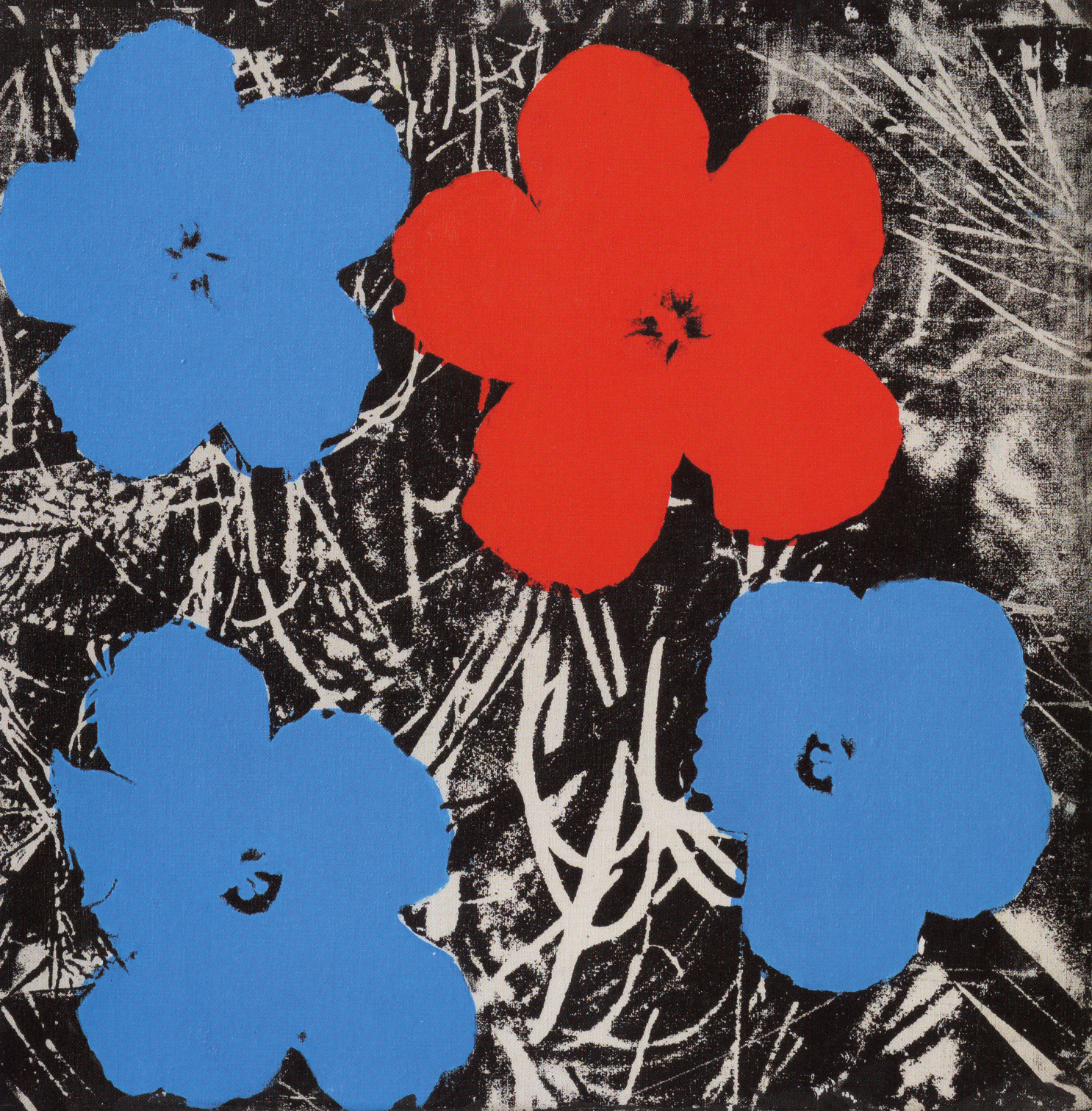

Figure 2 Elaine Sturtevant, Warhol Flowers, 1964–65. Synthetic polymer screenprint on canvas. 56 x 56 cm.

The definition seems perverse and startlingly retrograde in relation to generations of avant-garde attacks on authorship, aura, originality, and the like. And yet its perversity speaks a double, if unwitting, truth. First, although VARA touches on many of the moral claims espoused by its civil law counterparts, the act’s definition of art largely avoids the implicit metaphysical claims for art and authorship in droit d’auteur, such as the “paternal” bond between artist and artwork. In our view, it appears to be anchored, like all U.S. copyright, in crude economic calculus: signed works of art existing in a single copy, or in a limited edition of two hundred copies or fewer, operate p. 12 differently in the capitalist marketplace and so demand different treatment by the law. Second, despite the endless avant-garde attacks on authorship, aura, originality, and so on, the unique or limited-edition work of art overwhelmingly retains its death grip on the market, museums, and academic discourse. The crude economic calculus in VARA yields a definition of “the artist” that is as clear as it is bleak: an artist is an author who makes little to no money from mass copies.

Elaine Sturtevant, Warhol Flowers, 1964–65. Synthetic polymer screenprint on canvas. 56 x 56 cm.

The definition seems perverse and startlingly retrograde in relation to generations of avant-garde attacks on authorship, aura, originality, and the like. And yet its perversity speaks a double, if unwitting, truth. First, although VARA touches on many of the moral claims espoused by its civil law counterparts, the act’s definition of art largely avoids the implicit metaphysical claims for art and authorship in droit d’auteur, such as the “paternal” bond between artist and artwork. In our view, it appears to be anchored, like all U.S. copyright, in crude economic calculus: signed works of art existing in a single copy, or in a limited edition of two hundred copies or fewer, operate p. 12 differently in the capitalist marketplace and so demand different treatment by the law. Second, despite the endless avant-garde attacks on authorship, aura, originality, and so on, the unique or limited-edition work of art overwhelmingly retains its death grip on the market, museums, and academic discourse. The crude economic calculus in VARA yields a definition of “the artist” that is as clear as it is bleak: an artist is an author who makes little to no money from mass copies.

This recognition elucidates a profound misalignment with copyright law. Copyright law is about—well—copies. But the art market prizes scarcity rather than volume and originals rather than copies. Although individual songs or books or movies are perfect substitutes for one another, the distinction between originals and copies forms the very foundation of the art market. Today, visual artists derive the overwhelming majority of their art income not from copies but from the sale of original works—typically unique or limited editions. Unlike markets for other creative works, copies play almost no economic role in the art market; when they do, the role is surprisingly trivial. Despite the mind-numbing popular discourse focusing on superstar artists and art as an “investment vehicle,” the vast majority of works of art have no resale market at all, let alone a market for copies or derivative works (such as prints, postcards, or T-shirts). To economically sustain themselves, artists instead must recoup the costs of their production and derive income from the initial sale of a piece. Even for the tiny fraction of highly successful artists who do have a market for copies or derivatives of their work, those income streams are trivial when compared to the money derived from first sales. For example, the Andy Warhol Foundation makes a few million dollars a year from licensing Warhol’s artwork to appear on everything from T-shirts to snowboards. But that figure—based on the licensing income from copyrights for every single work of art in Warhol’s vast oeuvre—pales in comparison to the multi-million-dollar prices fetched by individual Warhol canvases at auction or in private sales. And remember: the Warhol Foundation, with its rich licensing market, is a unicorn in this story. Most artists or estates have no market for copies or derivatives. Therefore, an exclusive right to make copies p. 13 does not provide an economic incentive to visual artists. (For a more thorough elaboration of this part of the argument, supported by extensive empirical references, see Adler, “Why Art Does Not Need Copyright,” 329–343.)

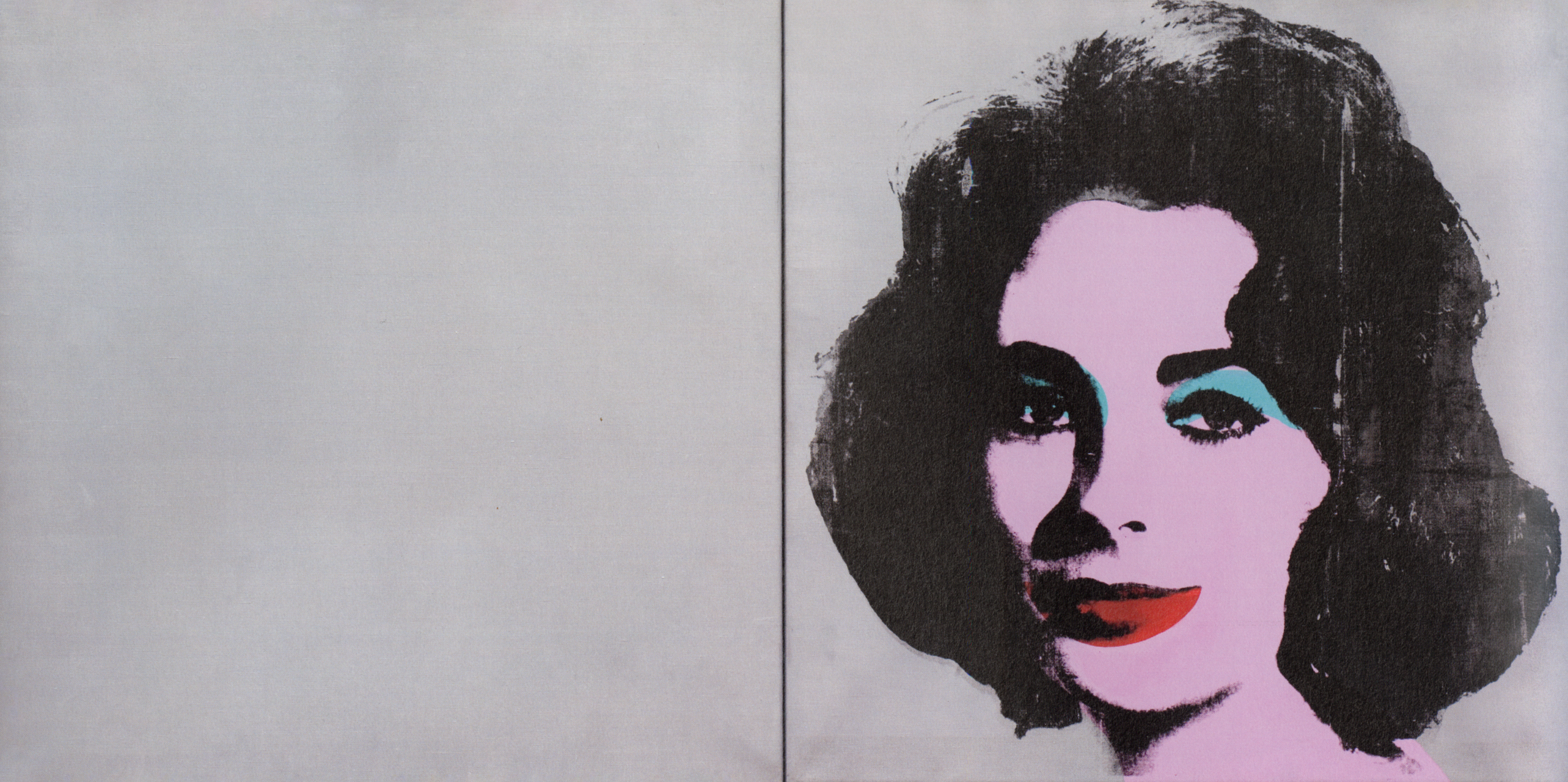

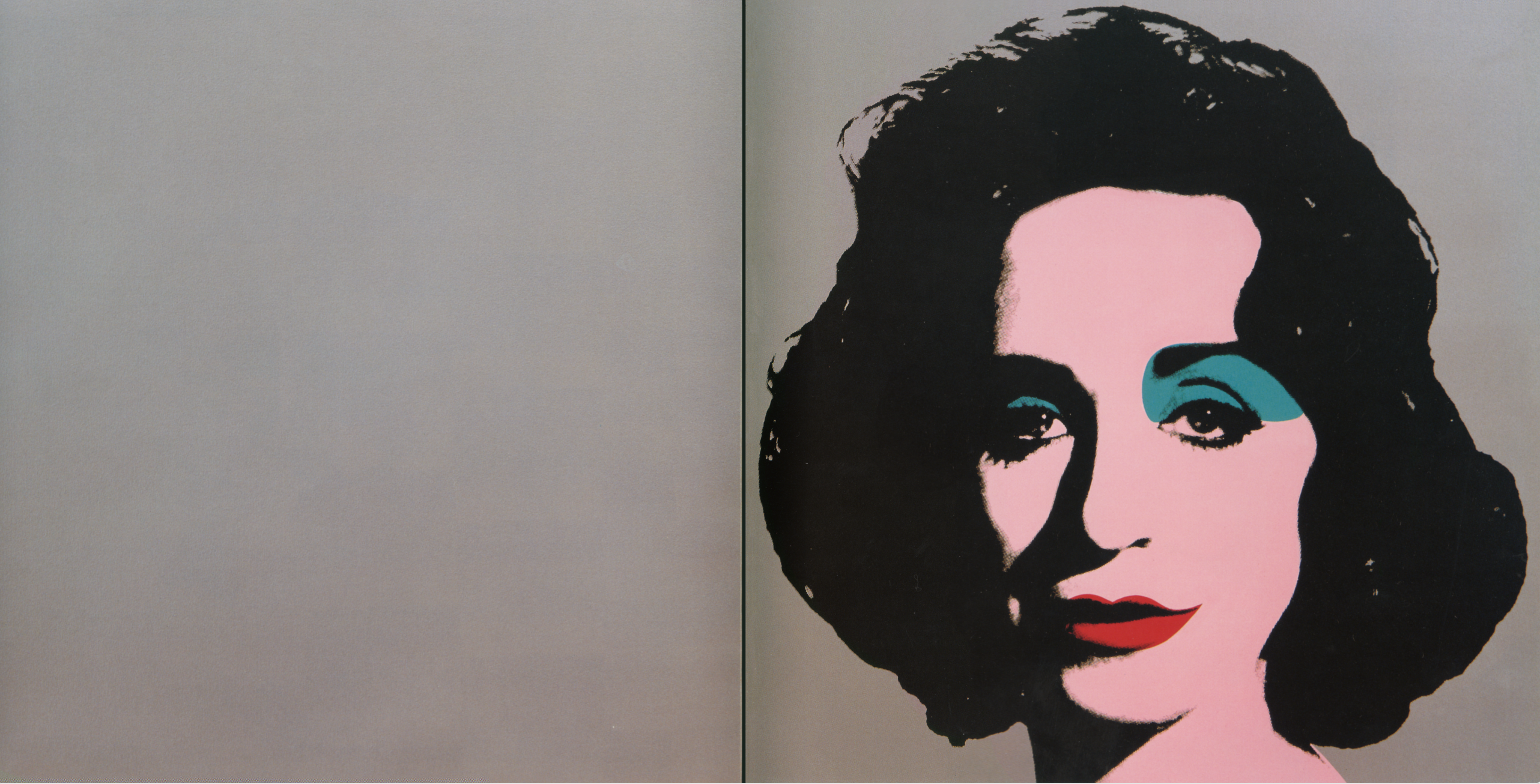

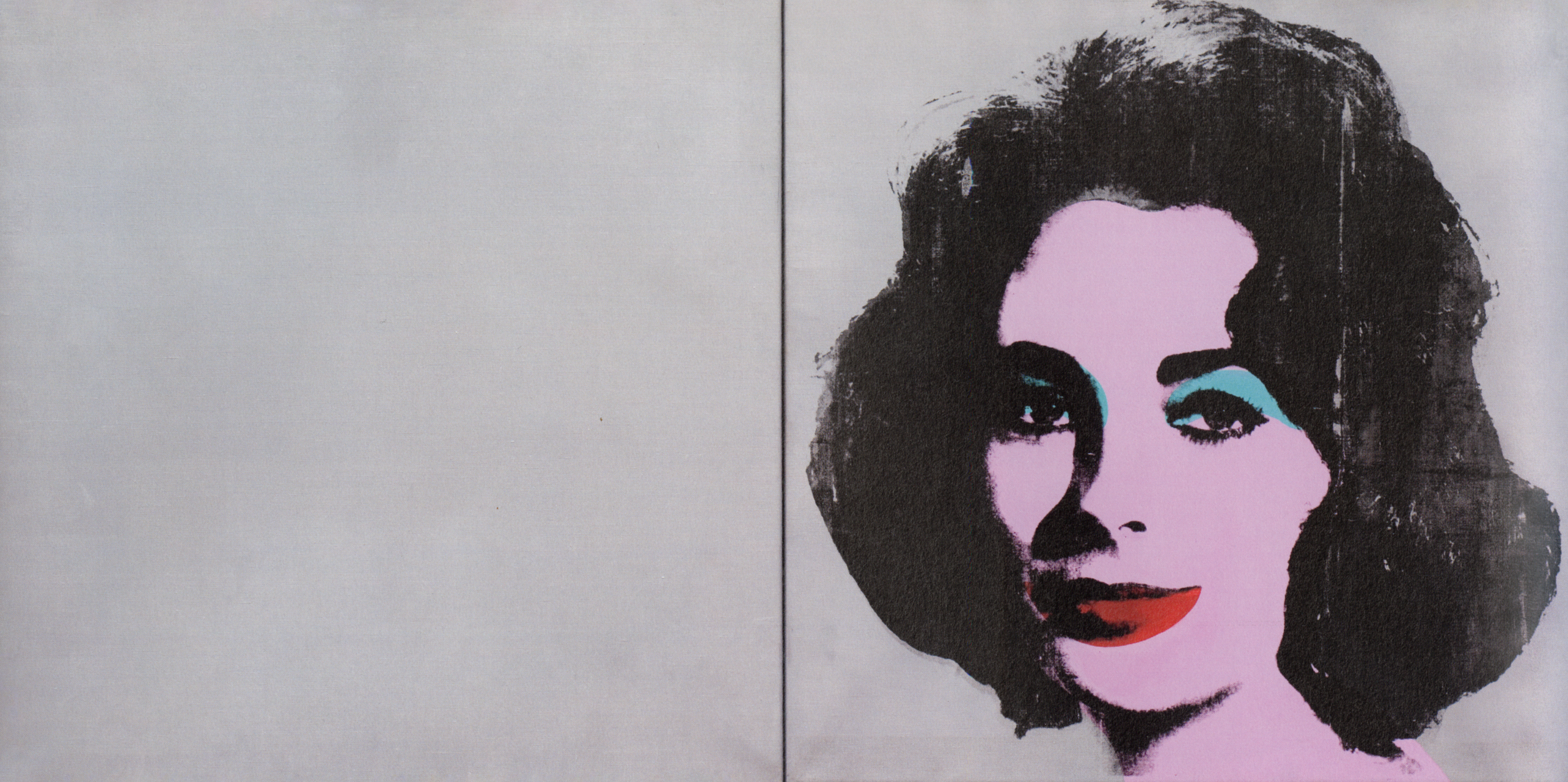

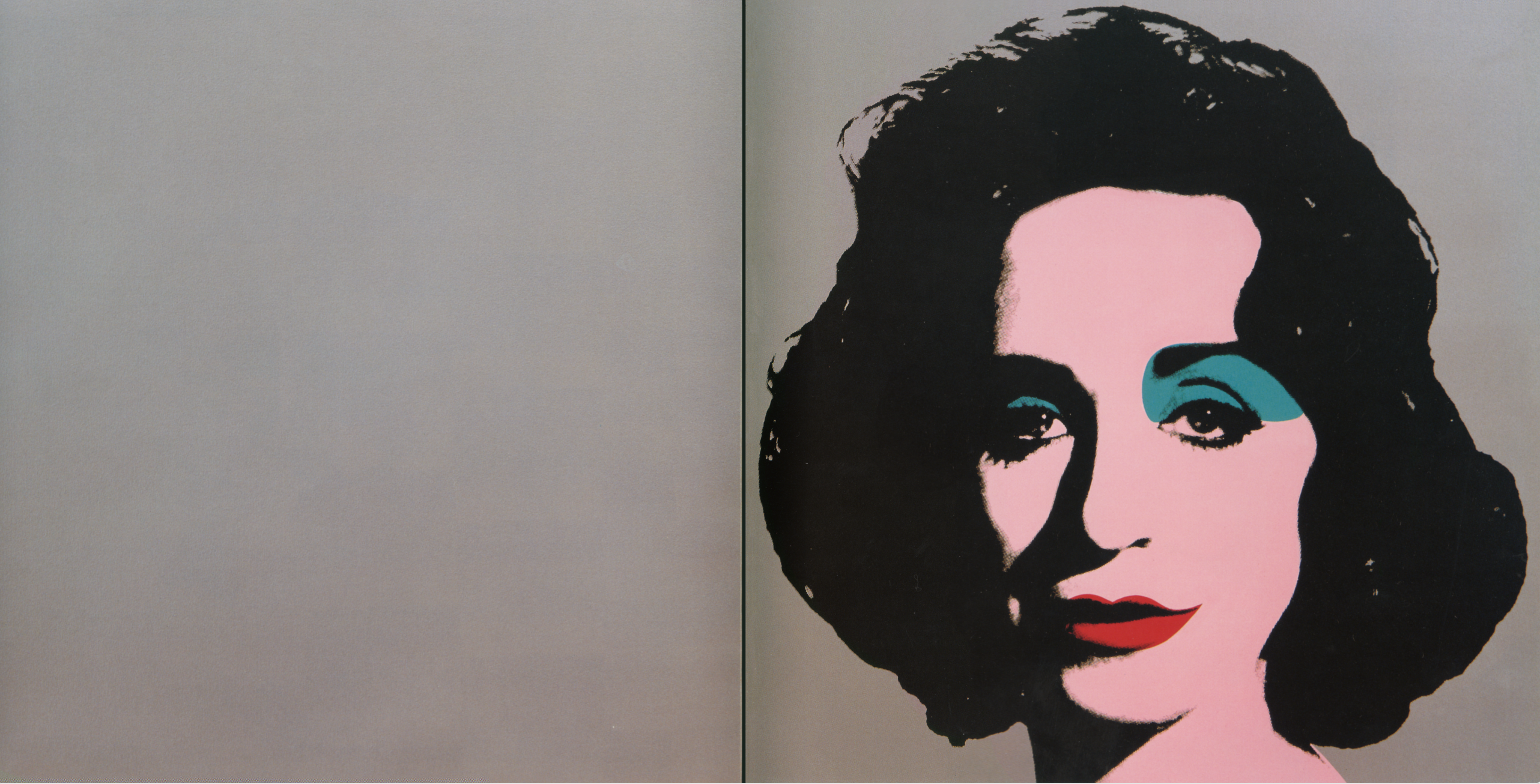

Figure 3 Andy Warhol, Silver Liz (diptych), 1963. Silkscreen ink, acrylic, and spray paint on linen. Two panels, 40 x 40 in. each.Figure 4

Andy Warhol, Silver Liz (diptych), 1963. Silkscreen ink, acrylic, and spray paint on linen. Two panels, 40 x 40 in. each.Figure 4 Deborah Kass, Double Silver Deb, 2000. Silkscreen ink and acrylic on canvas. Two panels, 40 x 40 in. each.

VARA’s insistence on signed works points to yet another brute reality suppressed by most readings of art and copyright. As argued by Xiyin Tang in her contribution to this issue of the journal, artist signatures function like trademarks, and artworks function like luxury goods. In his article, Elcott demonstrates that this is not a recent phenomenon but rather is endemic to the history of art, especially modern art. A signed doodle by Pablo Picasso has vastly more economic value than even the most meticulous copies of his acknowledged masterpieces.

Deborah Kass, Double Silver Deb, 2000. Silkscreen ink and acrylic on canvas. Two panels, 40 x 40 in. each.

VARA’s insistence on signed works points to yet another brute reality suppressed by most readings of art and copyright. As argued by Xiyin Tang in her contribution to this issue of the journal, artist signatures function like trademarks, and artworks function like luxury goods. In his article, Elcott demonstrates that this is not a recent phenomenon but rather is endemic to the history of art, especially modern art. A signed doodle by Pablo Picasso has vastly more economic value than even the most meticulous copies of his acknowledged masterpieces.

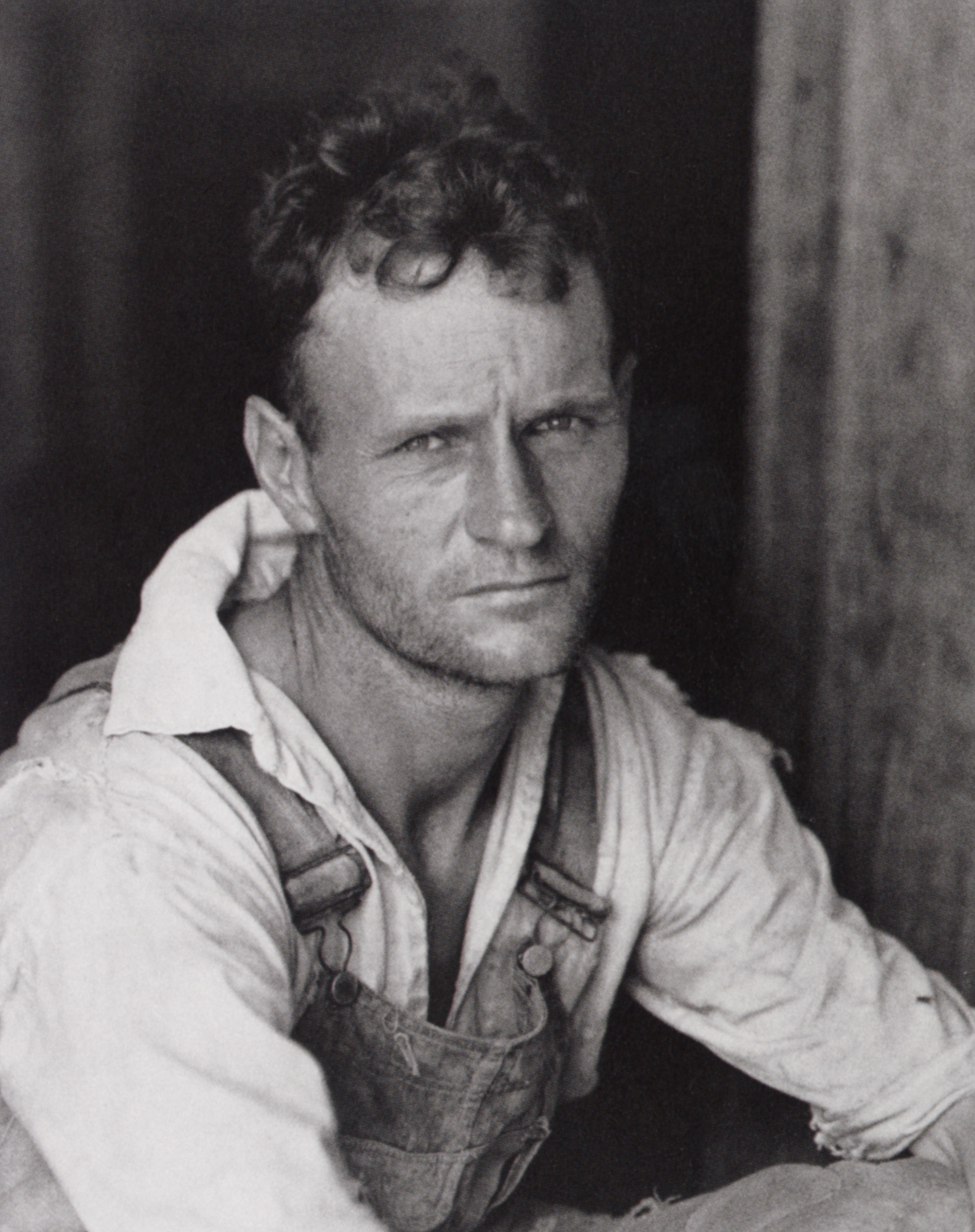

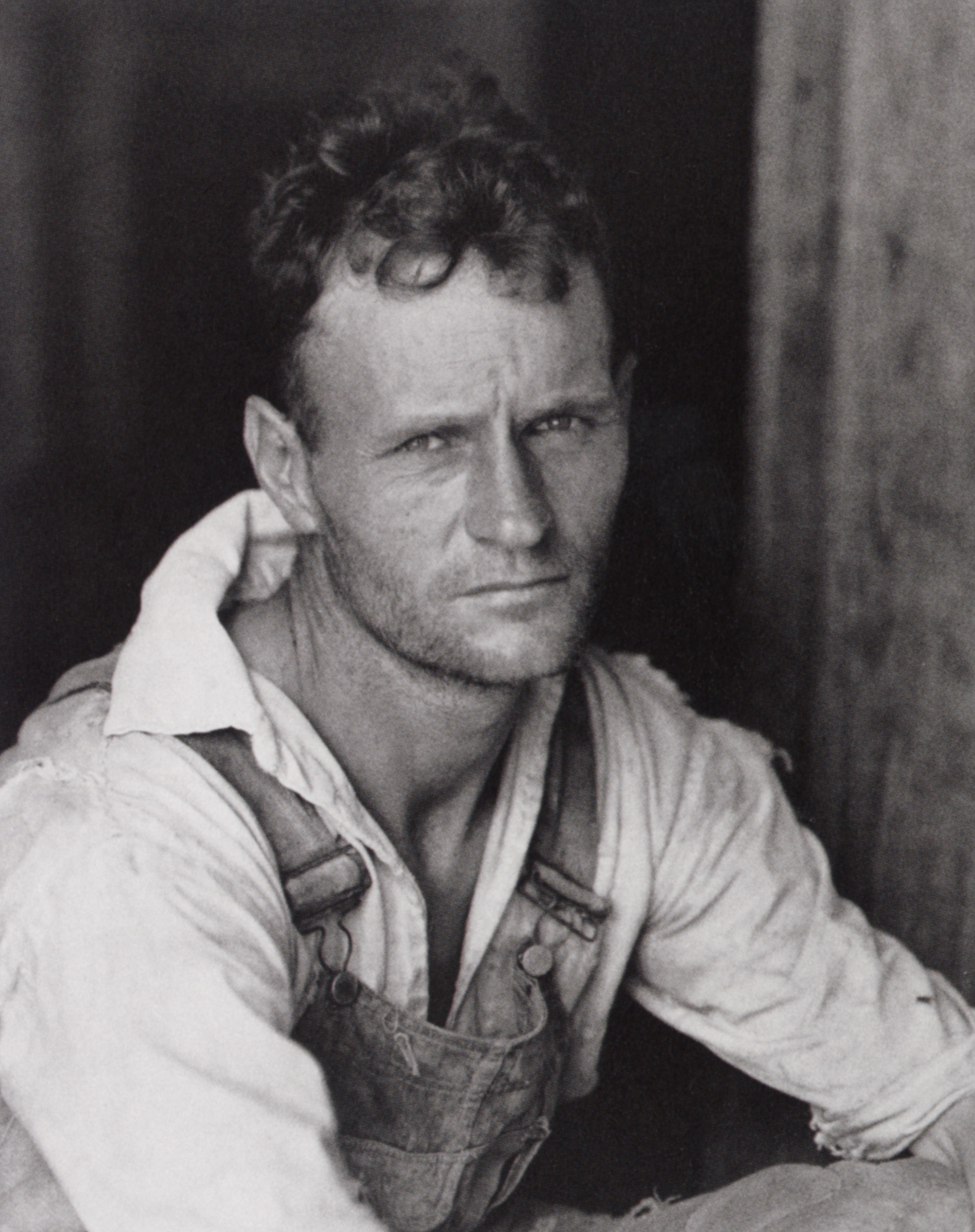

Copyright fails to provide a pecuniary benefit to visual artists and thus does not incentivize them to create. But copyright is also unnecessary to ensure that artists are not disincentivized from creating, which is a further concern of copyright theory. A core premise of copyright law—that the unauthorized copy poses a threat to creativity—does not apply to visual art. This is because the art market already has a powerful mechanism in place that legal scholars have ignored and that obviates the need for copyright: namely, the norm of authenticity, which forms the foundation of the art market, making copyright superfluous.19 The market’s insistence on authenticity ensures that even if an artist’s content is “stolen,” the “thief” cannot misappropriate the economic value of the work. A copy of a Warhol or a Warhol-style work, so long as it is not sold as an actual Warhol, has effectively no market value—unless executed by someone like Elaine Sturtevant or Deborah Kass—and in no case could it compete with let alone supersede Warhol’s market. Recall that the reason we grant copyright is to ward off economic substitution, which would deprive an artist of the economic incentive to create. But the art market’s insistence on authenticity, by tying a work’s value to the identity of the artist and policing the market by separating the real from the fake, already ensures that even a perfect copy (unless it is an undetected forgery) cannot serve as a market substitute for the original artist. Thus, for example, the market for Sherrie Levine’s After Walker Evans, a p. 14 series of re-photographs she took of canonical photographs by U.S. documentary photographer Walker Evans, differs from the market for Evans’s “original” photographs.

Figure 5 Walker Evans, Floyd Burroughs, cotton sharecropper. Hale County, Alabama, Summer 1936. Gelatin silver print.Figure 6

Walker Evans, Floyd Burroughs, cotton sharecropper. Hale County, Alabama, Summer 1936. Gelatin silver print.Figure 6 Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans no. 3, 1981. Gelatin silver print.

Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans no. 3, 1981. Gelatin silver print.

The utilitarian account of copyright has always acknowledged a tradeoff between costs and benefits in granting copyright to authors. The limited monopoly granted by copyright, while supposedly necessary for creative works to be produced, comes with the cost of preventing others from accessing and building on those works to create new ones. But given the lack of benefits copyright confers on the visual arts, we are left only with costs. And the costs in this realm are considerable and largely invisible.

These costs are borne not only by artists, for whom copyright presents a barrier to artistic borrowing, including the practice of appropriation, but also, with almost no visibility, by art historians, curators, writers, and other arts professionals who depend on reproducing images for their work.20 Copyright thwarts them either because the costs of permissions for licensing images is exorbitant relative to the project or because rightsholders simply refuse permission. Sometimes refusals of permission occur because rights- holders disagree with the content of the scholarship, thus giving copyright holders a power to censor, effectively and invisibly, certain kinds of scholarship and criticism. (See, for example, the infamous instance where art historian Carol Armstrong was forced to publish an article on photographer Diane Arbus in the journal October without any images.21 The editorial note is a rare instance in which a scholar and scholarly publication refused to succumb silently to permissions blackmail.) Many of the uses for which art historians and publishers pay—or are forced to avoid—should be protected by the fair use doctrine, at least in theory. But given the uncertainty of that doctrine and the prohibitive costs of litigation, publishers typically require scholars and curators to seek permissions p. 15 rather than risk lawsuits. A 2014 study gave a rare glimpse of the costs copyright imposes on scholars:

Art historians have found it necessary to pay licensing fees from their own pockets—in one case, $20,000 for a single book—for permissions. They avoid writing surveys and historically oriented texts, which are permissions heavy, and often steer clear of the last hundred years of artistic production. They warn graduate students against pursuing certain topics.22

Because of copyright, entire subjects of scholarship and criticism may be missing from the record, as art historians avoid or are forced to abandon work because of copyright problems. The 2014 study found that a majority of arts editors and publishers have “avoided or abandoned a project for copyright reasons” and that the costs fall disproportionately on those with the least resources: “graduate students, junior faculty, and academics at institutions that do not cover permissions costs, along with scholars and independent curators, who only sometimes receive help from editors and institutions.”23 Thus, the decision to copyright visual art, which is unnecessary according to the logic of copyright itself, coupled with the climate of fear that surrounds fair use law, has distorted not only art but also art history.

Remarkably, the cost to art historians, artists, and other arts professionals is mostly invisible to lawyers. It appears nowhere in the case law for the simple reason that copyright wielded in this realm never rises to the level of litigation and, given the economics of the art and publishing industries, probably never will. Visual art copyright battles in the reported case law read like a who’s who of the top 0.001 percent of artists, with multiple cases fought by Richard Prince (who has been sued three times), Jeff Koons (five), and the Warhol Foundation (resulting in the Supreme Court case that is the subject of our roundtable). These artists occupy a disproportionate place in the case law both because their wealth makes them targets for lawsuits and also because they have the funds to defend themselves rather than fold when sued. But in the shadow of these giants, copyright exerts tremendous power over the working lives of scholars, curators, and the 99 percent of all artists who do not have a team that can do the labor of seeking licensing and permissions, with lawyers at the ready and the resources to go to court or even to respond to a cease and desist letter. The roundtable discussion in this issue of the journal sheds important light on the near total disconnect between the lived reality of working artists and U.S. copyright cases, including the recent Supreme Court Warhol decision. The 99 percent of artists—and scholars—face a choice when denied a license for copyrighted imagery: succumb to potential copyright blackmail; risk litigation, which could be p. 16 bankruptcy-inducing even if one ultimately prevails; or simply avoid certain kinds of work.24

| | | | |

Figure 7 October no. 66 (Fall 1993): 28.Figure 8

October no. 66 (Fall 1993): 28.Figure 8 October no. 66 (Fall 1993): 30.

October no. 66 (Fall 1993): 30.

Art and law intersect across a range of discrete and overlapping domains. An exhaustive account of these intersections is impossible. Instead, part of this special issue gathers short essays on a range of convergences between art and law beyond copyright. These texts offer succinct introductions, essential references, and suggestive glimpses into topics ripe for further art-historical and legal inquiry, including moral rights, design patents, contracts, trademarks, right of publicity, cultural heritage, and copyright and AI.25 Additionally, as argued at greater length and with considerable historical and archival depth, Anne Hilker points to the centrality of tax law in the foundation and evolution of museums in the United States. For good reason, the legal departments of U.S. art museums are staffed less by intellectual property and copyright lawyers than by trusts and estates lawyers. More important, as she argues, not only did tax law shape U.S. museums, but museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art shaped U.S. tax law. Finally, in his extended study of Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), which is steeped in ascendant French and international trademark law, Elcott demonstrates art’s capacity and need to engage and interrogate wide-ranging facets of intellectual property beyond copyright. p. 17

A cornucopia of impressive legal and art-historical scholarship on art, copyright, and authorship is a testament to the strength of the field.26 And yet there is more to art than authorship. Individually and in aggregate, the articles offered here expand the nexus of art and law far beyond copyright and authorship. They also reject the autonomy of art and insist on its imbrications in economic, political, and legal systems that perpetually pressure its practices, distributions, receptions, and boundaries. At the same time, the articles and roundtable show the necessity of rejecting the autonomy of law. As a baseline, courts must stop deciding copyright cases as if the lived reality of artists is represented by figures like Warhol, Koons, and Prince. More broadly, the contents of this special issue model not only how the law shapes art but also how art informs and interrogates diverse branches of the law, from copyright to design patents, contracts to tax law, trademarks to rights of publicity, moral rights to cultural heritage, and beyond. Just as we invite art lawyers to continue to press beyond copyright and delve more deeply into the histories and practices of art, so, too, we invite art historians to attend to the multifarious convergences of art and law beyond the well-worn realms of copyright and authorship.

“Art beyond Copyright” does not aim to be the final word on art and law. Quite the contrary. Our hope is that the questions and issues raised in this volume and the interdisciplinary approach we take here will spur new conversations and debates in the worlds of art, law, and their myriad intersections.